The Mughal Matriarchs - Power & Reign of the Mughal Zenankhana

Just as I had convinced myself by the time I went to 10th grade that the 16th and 17th century India for Islamic women was doomed, something inside me had a gentle urge to go beyond the school history textbooks and dig in a little deeper. I felt that the truth lies differently somewhere. When we think of the word ‘harem’ or ‘zenana’, we instantly think about how women would be objectified or were being treated as a showpiece with null values and respect for their thoughts by the patriarchy. But some 16th century texts say otherwise. While, I personally agree that not all Timurid women (by birth or by marriage) were treated rightfully and equally, some of them did stand out of the crowd and were considered of higher status in the Mughal courts, even more than the reigning Padshahs. The Mughals made an entry in Hindustan in the first battle of Panipat by defeating the then Afghani Sultan of Delhi, Ibrahim Lodi. Now, when we speak of men and their respective reigns, the women are side-lined and very little information is known about them.

When the successor of Tamerlane; Babur made India his home, he not only brought with him the horses and warriors but also his zenana which included elderly women, young wives, children, servants, divorced sisters, widows and unmarried relatives. These mighty women mostly spent their lifetime in tents and riding on horses with their men, travelling far distances. Babur’s elder sister Khanzada rode horseback to Hindustan because of the obvious sacrifice she had to make early in her life when she was left behind with the Uzbek warlord Shaybani Khan for the safety and security of her younger brother. The Mughals were very proud of their women clan, who also made important decisions and played significant roles in the courts, these women also took hardships, and willing to suffer for their menfolks in order to keep them safe.

When Khanzada at an elderly age of 65 rode from Kandahar to Kabul in the court of Kamran Mirza, she also carried with her the harem’s desire for reconciliation by also representing as Padshah’s ambassador. Maham Begum, Dildar Begum, and Gulrukh Begum, Babur’s principal wives along with Gulnar Agacha and Nargul Agacha (concubines), bore his children even as they constantly travelled, almost constantly harassed by enemies. The resources and material available about these women is available for the common man to read but they are just plainly ignored. Babur’s maternal grandmother was of strong influence on him. “Few amongst women will have been my grandmother’s equals for judgement and counsel; she was very wise and far sighted and most affairs of mine were carried through her advice.” he writes.

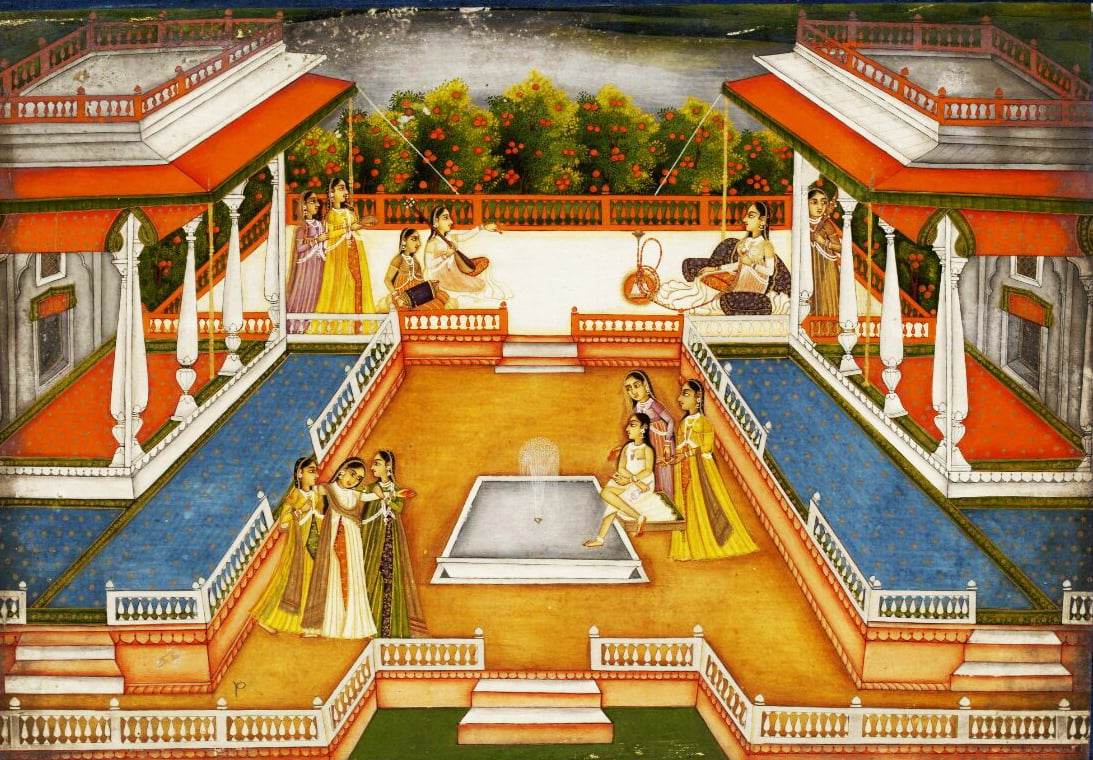

An outstanding document exists which was discovered and translated from Persian to English in the early 20th century. Gulbadan Bano, sister of Humayun and daughter of Humayun arrived in Hindustan at the age of five. Many decades later, Akbar; her grandnephew asked her to write a biography account of Babur and Humayun. Gulbadan’s first-hand account; the ‘Humayun-nama’ also speak about the haraman of the sixteenth century. The few details known to the audience about Bega Begum; Humayun’s first wife also reach out to the common masses due to these accounts written by Gulbadan; Humayun’s bitter-sweet relationship with her, his opium habit, despite being contrast to each other’s personalities, she was a loyal custodian of his reign and legacy. Because of Gulbadan’s close relationship with her sister in law, Hamida Bano who was much younger to the then wandering future Shahenshah, we also learn about their courtship and later a marriage much to Hamida’s dismay who took forty days to accept the proposal by Humayun, 14 years her senior. She traveled with Humayun to Persia, who was then in exile in Shah Tahmasp’s court. Through Gulbadan’s account, and Humayun’s attendant Jauhar, we see a different change in the haraman. A small rugged space where purdahs for women exists and there no rigid limitations to freedom of women and these women are constantly called upon to play their duties in the Mughal courts. The courts are a strident place with disagreements, discussions, music and laughter.

Akbar’s reign brought a drastic change in the harem who made this a little bit more separated and isolated space for women. Akbar married many women in which most of them also were performed due to alliances of two kingdoms to rule in peace under his rule. These marriages were also with Rajput women who also brought along with them the grandeur, their brothers who later worked under Akbar in his court. It was during his time that to maintain the privacy and anonymity of these women, they were now given titles. Maryam Makani (of Mary’s Stature) for Hamida Bano, Akbar’s mother and Maryam - uz Zamani (Mary of the World) for Jehangir’s mother, Harkha Bai. The identity of Jehangir’s mother was surrounded by myths that by all contemporary writers it was written that she was known as ‘Jodh Bai’ which is untrue. Hidden behind her title, this Rajput princess became an intimidating and independent wealthy matron, who traded her own ships in the dangerous and pirate infested waters of the sixteenth century.

Abd-al-Qadir-Badayuni, a historian in Akbar’s court was of an orthodox spirit. His great misfortune was to be a contemporary and biographer for a much liberal, curious padshah as Akbar. For someone as orthodox as him, to write about the slow spreading Hindu Rajput influence at Akbar’s court was not exactly his ideal thought. But, through his consistent appalled accounts, we also learn that these Rajput women in the padshah’s court and in particular Harkha; brought with them the Vedic fires, worshipping of sun, vegetarian diets, marriage rituals and fasting, Rajasthani grandeur and couture.

Akbar was left in a safe company of women when Hamida Bano and Humayun were forced into exile by Sher Shah Suri. These women happily took active part in roles to take care and nurse of the future padshah of Hindustan. Some of these also nursed him through his infancy, were his milk mothers or ‘angas’. Chaos returned after Humayun’s death after regaining his position as the Padshah-Ghazi of Hindustan again and Akbar was made to sit on the throne at a mere age of thirteen. Through his adolescence and childhood years, he majorly depended on his milk mothers for support, loyalty and guidance. One of them which most of us know well is ‘Maham Anaga’, who became extremely powerful as Akbar put immense faith in her judgement and ability. She was politically ambitious, and at one point was also known as the ‘vakil’, she later became a patron for the Khair-ul-Manazil Mosque in Delhi.

Salima Sultan was the widow of Bairam Khan, Akbar’s commander in chief in the army. Akbar later married her only for propriety and they bore no children together. But, her influence in the Mughal court is widely seen, as she performed Hajj pilgrimage with Gulbadan which lasted for seven turbulent years. She succeed in the impossible reconciliation of Jehangir and his father, after Jehangir committed a heinous crime and the rest thought that the son would never be forgiven. The zenana which was once filled with influence of the older Turki speaking matriarchs of mighty Timurids had died out. They were replaced by the Rajput and Persian women, no longer the Chagatai Turkish ones. Through the 200 years of life-span of this empire in Hindustan, only one woman was given the title of ‘Padshah Begum’ which was usually retained by her until she died. This was usually given to those women of enormous prestige and respect.

Mughals were very welcoming of women with talent, charisma and ambitions. One of the most disputed women to hold this title was Noor Jahan. We find a major change in the pattern of the zenana when at times, the women to hold this title were not royal at all. They were foster mothers and Persian refugee women; and two of them were Mumtaz Mahal and Noor Jahan. One account mentions of the English ambassador Thomas Roe who realised that he has to interact with Noor Jahan to conduct trade in Hindustan. In comparison to these women, the English women were expected to lay low and be subordinative. Dealing with these mighty and powerful Hindustani women, caused much resentment and bitterness among the European commentators. When we read Mughal history, much of it is distorted by the Eurocentric ideologies. The access to many documents written by Indians on contemporary Mughal history becomes harder as most of them written in Urdu and Persian also remain untranslated.

Most women, unlike what the audience is being told weren’t wives at all. But there were mothers like Hamida Bano and Harkha, unmarried sisters like Jahanara and Roshanara, divorcees like Khanzada, single daughters like Zeb-un-Nisa and Zeenat-un-Nisa, aunts like Gulbadan, and distant relatives like Salima Sultan. They all had significant roles to play and duties to perform, they were respected and paid for these crucial jobs. In fact, it is wrongly portrayed that the women in the harem were only kept to satisfy the needs of men in power. In this span of 200 years, the era of these Mughal women changed as their influence and power over the court increased. The writing work of these women is less appreciated; Gulbadan’s accounts of ‘Humayun-Nama-, Jahanara’s incessant love for Sufism and her writings. Her correspondence was not only with kings wanting her help with financial aid but also her brothers Aurangzeb and Dara Shikoh, she became a point of succession between her brothers who sought her help. Many of these women, including Aurangzeb’s daughter Zeb-un-Nisa wrote poetry too. These women wrote farmans, orders, and had seals in their names.

‘By the light of the sun of the emperor Jahangir, the bezel of the seal of Noor Jahan, the Empress of the age has become resplendent like the moon’ is a very powerful testimony by Noor of her own ambition. Even though we fairly have less paintings available of these women, their mentions in these accounts remains unquestionably important. Often as the Mughals are credited for their grandeur, the women remain forgotten indeed who originally shaped its formation, the increased wealth and ruthless ambitions.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, an English woman accompanying her husband to the Ottoman Empire in the eighteenth century was astonished to see that these Muslim women, married as well as unmarried, were having full financial control over their own wealth, unlike their sisters in their own religion. Mughal women meanwhile, earned an income through cash. Active participation was taken by Jahanara and Maryam-uz-Zamani in international trade which thereby increased their wealth. They had full freedom to spend it the way they wanted to and after their death they could also pass it on to the person of their own choice. The Mughals in contrast to their contemporaries, the Ottomans and Safavids remained highly respectful of the women, and also were highly faithful of their nomadic Timurid ancestors for whom divorce and remarriage was a normal way of life in a land constantly surrounded by war. Widows were encouraged to remarry, there was rare stigma attached to divorced women or even to the ones ‘taken' by their enemies, this became a major part of their culture. The influence and power of these women was highly respected by the Mughal courts and their increasing contributions to the Timurid legacy, they also took active part in ancient but the dangerous and volatile game of politics.

One of the most prodigious women who remains my personal favourite is Jahanara. When Shah Jahan moved his capital to Delhi, an entire new city of Shahjahanabad (present day old Delhi) was built. The architect of the popular place Chandni Chowk is no other than her. With unimaginable wealth at their disposal, they created a vision of an entire city which was considered nothing but a paradise on earth. I can personally speak and write about Jahanara’s accomplishments, but that would all feel less. She was a Sufi poet and scholar, she was also a writer, a poet and a patron for writers and saints. A builder with enormous ambition, who shaped Shahjahanabad, unfortunately, most of now is gone. Destroyed by the British in the violent 1857 Uprising. I’d fondly speak more of Jahanara’s contribution in the administration and her patronage towards arts in my next article.

As much as the contribution of the Mughal reign remains forever in our books, the women who shaped the 200 years old history of India, sometimes subtly, sometimes ruthlessly and sometimes extraordinarily, should be celebrated. But more importance is given to the love stories, and little much to how much in abundance they contributed in building of a vast empire. I am sure, the way my curiosity drove me to start my research on these majestic and powerful women, who were nothing but full of ambition, desires and their strong independency, most of us remain curious to understand the Zenana and remove the preconceived notions we have since our childhood. It’s in our best interest to go beyond the conventional books and the stereotypical theories which we are made to believe in. The outstanding contribution of these strong headed women of the Baburid dynasty stands out amongst the rest.

Sanika Devdikar

workwithsanika@gmail.com

_Bibliography :

Daughters of the Sun - Ira Mukhoty

References from :

_Akbarnama by Abu’l-Fazl ibn Mubarak

Baburnama - Babur

Tuzuk - I - Jahangiri - Jahangir

_Humayunama - Gulbadan Sahiba Begum_